I have given you Shechem – one portion more than your brothers, which I took from the hand of the Emorites with my sword and my bow.

Meshech Chochmah: Onkelos changes “my sword” and “my bow” to tzalusi / my prayer and ba’usi / my supplication. These prayer-words are not synonyms. They reflect two entirely different modes of conversation with HKBH.

Tzalusa refers to our fixed prayer, which is structured, and obeys a given form. In all such fixed prayer, i.e. the shemonah esreh that we daven three times daily, we must precede our list of requests with praise of Hashem, and follow it with thanks. If we tamper with the fixed content or even the formulas that express it, halachah tells us that we have not fulfilled our obligation.

Ba’usa, on the other hand, is free-style. It pops up even where you might not expect it. The gemara[2] allows for it, for example, even within the structure of our fixed prayer. If we wish to innovate, we may add our own thoughts and prayers within each berachah of shemonah esreh, so long as our innovation is related to the specified topic of that berachah. What we say and how we say it, however, remains our choice. There are no givens. We can formulate our autonomous prayer any way we wish.

The two modes could not be more different. Our fixed prayer is part of our designated avodah, our service of Hashem. While kavanah enhances the performance of any mitzvah, it can still be minimally fulfilled simply with the intent to perform Hashem’s commandment. Our fixed prayer is not so different. Minimal intention suffices to at least fulfill the requirement of prayer, namely, kavanah in the first berachah, and a very limited degree of kavanah thereafter.

Personal, optional prayer is subject to stricter demands. To be effective, it requires full focus and attention, and knowledge of the meaning of the words. (This might be the intention of the gemara[3] that a person’s prayer is heard only if he places his heart in his hands. In other words, he needs to fully direct his heart to Hashem.)

Our fixed prayer revolves around the community, the tzibbur. It is best said together with others; the language is that of the group, not the individual. The gemara points to a seeming contradiction between prayer that is said to be unacceptable without full sincerity and that which is accepted despite shortcomings. The solution, claims the gemara,[4] is that the latter applies to group prayer, to the tzibbur. The point is that the group davening is our fixed, established prayer, which is not as demanding of kavanah as the prayer of the individual.

We now understand why Yaakov spoke of his davening specifically as “sword” and “bow.” He wished to accentuate the differences between the modes of prayer. The blade of a sword is inherently dangerous. It requires very little effort to cause great damage. Simply grazing it can be injurious, even fatal.

Arrows are quite different. They are as potent as the force applied to the bow-string, no more and no less. The arrows are as deadly as the effort put into them. Yaakov attributed his military victory over the city of Shechem (against great odds, and in standing up to the counterattacks of Shechem’s neighbors and allies) to the success of both modes of davening in which he engaged.

The gemara[5] praises the potency of the Shema recited on one’s bed before nodding off. It speaks of it not only as a sword, but as a double-edged one. The moments in which a curtain of sleep falls over a person are not well-suited for focus and kavanah. The Shema is recited as a formula, not with a great surfeit of concentration. The gemara therefore underscores that it, too, is part of our daily avodah, and therefore blessed with potency, even when lacking in kavanah.

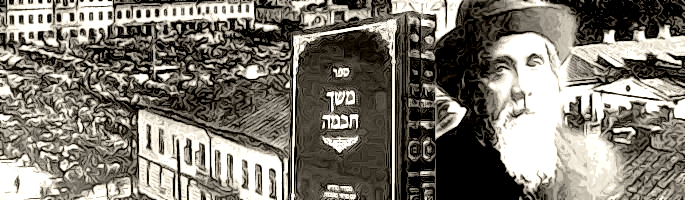

[1] Based on Meshech Chochmah, Bereishis 48:22

[2] Avodah Zarah 8A. See Eichah 3:41

[3] Taanis 8A

[4] Loc. cit.

[5] Berachos 5A